Say what? It's true I’ve drifted away from the practice of landscape architecture and more into marketing in recent years, but even so I’m wondering how it is I’ve kept at least one foot in the profession for decades now and still I’m thinking, “Winter watering? That’s a thing? Really?” For the record, this was also news to several of my fellow landscape architects at BRECKON landdesign. And yes, according to Scott Lebsack, RLA, of our Twin Falls office, winter watering most definitely IS a thing. In fact, it can be particularly important in high desert climates like ours that tend towards the cold and dry. In Idaho and other intermountain states, factors such as dry air and soils, low precipitation, and fluctuating temperatures, compounded by scant snow cover, can damage certain plants if supplemental water is not provided. Now that I think on it, this is a solid theory as to why the Schipka Laurel under the front eaves of my house have failed to thrive for two summers in a row. Winter drought damage – primarily to roots – is often invisible. That is, plants appear healthy enough, and use nutrients stored in their roots to fuel springtime growth. They then become stressed when summer temperatures rise and damaged root systems prove inadequate to hotter, drier conditions. And it’s not any kind of revelation that weakened plants tend to suffer more from insect or disease problems. Plant types more vulnerable to winter damage when conditions are dry:

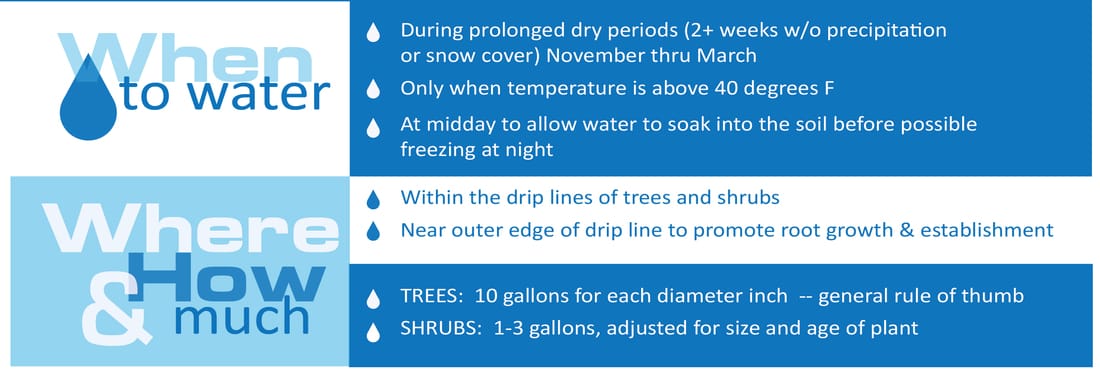

The latter almost always benefit from supplemental winter watering during establishment (typically defined as the one year period after planting). For young plants, supplemental water may not be a life-or-death issue, so much as the difference between thriving, or merely surviving, the first couple of winters. Winter watering also speeds plant establishment. So, now that we’re on to the potential benefits of supplemental watering during the colder months (and yes, be prepared to hook up that hose or schlep your watering can around if you’ve properly winterized your irrigation system), what’s the best way to go about it? Following are general guidelines for supplemental winter watering. And remember – an organic mulch layer (2-3" deep) is a great way to retain soil moisture and protect plant health during ALL seasons. Posted by Kim Warren

Sources: Klett, J. E. "Fall & Winter Watering, Fact Sheet No. 7.211." extension.colostate.edu. Colorado State University, Mar. 2013. Web. 22 Dec. 2016. Klett, J.E., and C. Wilson. "Winter Watering." Tall Timbers. N.p., July 2008. Web. 22 Dec. 2016.

0 Comments

Evergreens are essential to any planting plan because they provide structure and interest that persist through the winter. I recall a college planting design course where my professor described herbaceous plants as the ‘flesh’ of a landscape and evergreens as the ‘bones’ or ‘skeleton.’ I’ve always found this metaphor useful. And, as it seemed apropos of the season to feature something evergreen, I asked Scott Lebsack, RLA, of our Twin Falls office what he would recommend. Scott suggested Calocedrus decurrens, or Incense Cedar, a tall, narrow evergreen with fragrant foliage.  Miwok house of incense-cedar bark slabs. Photo by Jean Pawek. Miwok house of incense-cedar bark slabs. Photo by Jean Pawek. When crushed, the foliage has a strong incense-like aroma. Humans find the scent appealing, but deer tend to shy away from eating the leaves. Always a plus! Bark: Purplish-red, thin and scaly when young, increasing to several inches thick and developing into a rich brownish-red color with age. Mature bark is deeply furrowed, with interlacing ridges. Some California tribes used the rather formidable bark of Incense Cedar to build conical houses for autumn shelters during acorn-collecting season. Sun: Tolerates full sun in coastal climates. Best to have a bit of late-day shade from buildings or other trees in the Idaho desert. Water: Prefers drier areas for its native habitat and is thus well-suited to our desert climate. Under cultivation, adaptable to heat, drought, humidity and varied landscape conditions. Winter watering can be important with evergreen trees like Incense Cedar.

Size/Habit: 15-20’ tall, with a symmetrical narrow form. 8-10’ wide. In cultivated settings, may grow as high as 30-50’ with age. Landscape Uses: Privacy screen, windbreak, featured specimen Human-Plant Interactions: Practical ▪ Symbolic ▪ Medicinal A Natural Sauna Treatment for Your Stuffy Head. Because of its fresh, potent aroma Incense Cedar was used as an early form of aromatherapy. The Klamath Native Americans of southern Oregon created an herbal steam of branches and twigs to scent their sweat baths, while the Paiutes of the intermountain west inhaled an infusion of cedar leaves as a cold remedy. Still other tribes drank a decoction of the leaves to treat stomach upset. (We’ve said it before, but the medicinal uses mentioned are of purely anecdotal interest. Please stick to your corner drug store for what ails you.) Building Products Galore. In the modern world, incense Cedar is a commercial softwood species of some prominence. It is used for lumber, fence posts, railroad ties, Venetian blinds, siding and decking, and shingles. This is due to both its durability and decay-resistant properties. It is also used for cedar chests because the strong natural aroma of the wood is a deterrent to moths, which helps keep your clothes and linens un-holey. Please Bring a #2 Pencil. True or False: Incense Cedar is THE major source of wood for pencil stock in the United States. (True!) Care ▪ Propagation ▪ Pests The occasional disease, like dry pocket rot, can afflict Incense Cedar, but generally this has a greater impact on the quality of the wood, if harvested. It doesn’t significantly impact the health of the tree, so is of less concern to landscape architects and groundskeepers. Christmas Bonus! Parasitic mistletoe has been known to grow on Incense Cedar in native settings. Thankfully it causes little-to-no trouble for the tree. Bottom Line: Incense-ational This is an attractive, easy tree to grow, uses relatively little water after establishment, and boasts few problems or pests. Incense Cedar has a number of assets to recommend it, including its upright form, fragrant evergreen foliage, and deer resistance. In short, this tree would provide great ‘bones’ for any western landscape. Posted by Kim Warren |

AuthorsArchives

January 2017

Categories |

Portfolio |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed